|

Where billions go for a song.

Where billions go for a song.

|

|

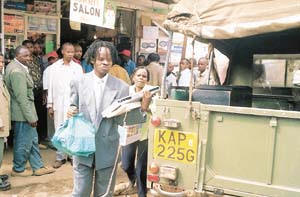

Bad Business: Artiste Poxi Presha and his vigilante group

seize counterfeit cass |

Singers and producers facing the music as 90 per cent of all

recordings sold in Kenya are pirated by cartels in India,

Pakistan, Dubai and Uganda, says World Bank report.

As night falls, the man

from River Road packs his wares in a plastic bag, deftly crosses

the busy streets and enters one of a string of bars in the heart

of Nairobi. His eyes dart from table to table, searching for a

willing buyer. He is also alert for any sign of trouble.

Satisfied that all is

well, he raises his voice: "Two for the price of one. Wide

selection here, both local and international. Cassettes, compact

disks, video tapes, name it..."

He says this in

sing-song. Like the pirated music that he sells, it is his

stock-in-trade. He is one among hundreds of hawkers in other bars,

open-air markets, shops and streets in Kenya.

Almost 90 per cent of

all music sold in the country is pirated, says a World Bank

report.

While artistes in other

African countries sell 50,000 to 200,000 cassettes of a new

release, those in Kenya barely manage 5,000 pieces. Compact discs

fare even worse. "Just about 500 units are sold," says John

Andrews of AI Records, a major distributor.

In six months, there

might not be a single genuine album on sale in Kenya, which is

reportedly worst hit in Africa alongside Nigeria.

Independent researchers

say live performances offer more financial gain to local artistes

than recorded material do. The World Bank report, "Value Chain

Analysis of Kenya's Music Industry," says that an artiste needs

only six live shows a year to earn more than the total sales of

his recorded music.

"Piracy is so rampant in

Kenya that people do not know any more what is legitimate," says

Andrews. He adds that his company has suffered a drastic reduction

in business. "We are doing less than one-tenth of the business we

did in 1985. It is that bad."

|

|

Bad Business: Artiste Poxi Presha and his vigilante group

seize counterfeit cassettes and recording equipment. |

The World Bank report was prepared by Global Development

Solutions LLC. But Andrews puts the figure of pirated music at 98

per cent.

"Top Kenyan musicians

should be millionaires, but they are not. You can see it for

yourself," he says.

As piracy takes a toll

on local music, international stakeholders are threatening drastic

action unless the Government acts.

Jennifer Shamalla,

general manager of the Music Copyright Society of Kenya, says: "It

has been recommended by the International Intellectual Property

Alliance that Kenya should be placed on the watch list."

But Andrews notes: "Our

problem is lack of implementation by the Government. There is a

gazetted copyright board but it has never sat since it was

constituted. How can the Copyright Act be useful?"

He is not the only one

pointing fingers at the authorities. Prechard Pouka Olang', the

director general of Talent Works and Rights Enforcement Ltd, says

the copyright board is ineffective.

Olang', popularly called

Poxi Presha, says the board was instituted in July 2003 but its

agenda has not been taken seriously. "For instance, a copyright

registration form should be signed by the board's executive

director. Yet the board has never had an executive director. It is

impossible to effect such requirement. Also, how can one contest

infringement on a copyright in court?"

An officer at the

copyright office at the Attorney-General's chambers admits the

board has been docile. He says steps are being taken to rectify

this.

"Our seeming dormancy is

borne by limited financial provisions. This year, we received Sh5

million from the Treasury to carry out a number of activities.

Proposals have also been made that senior officers of the board

sign copyright documents in the absence of an executive director,"

he says.

Poxi Presha is

vigorously fighting piracy through his vigilante organization.

After playing a leading part in popularizing local rap in the 90s,

he is identifying distribution networks of pirates and, with the

help of the police, conducting covert raids.

He says there are

illegal reproduction outfits in River Road, Parklands and

Kariobangi areas of Nairobi. Roof ceilings in shops and hotels,

and false walls in music outlets, are used to hide volumes of

pirated music.

Olang' recalls a raid on

a shop in Nairobi where they discovered that a shelf containing

genuine music was a door to a second shelf holding pirated

cassettes and CDs.

This frustrates the war

on piracy. "Some people in legitimate business are stocking

counterfeits," explains Shamalla. Basements of buildings in Ngara

estate are us ed to conduct illegal trade.

The World Bank report

lists Ngara and River Road as the trouble spots. It also mentions

Westlands and South "C" in Nairobi as key distribution points.

Nakuru, Mombasa, Eldoret

and Kisumu are also said to be active towns. From here, bogus

music is sold to consumers in pubs, bus termini, barber shops and

even butcheries. Bus termini are the most lucrative.

About 630 bus stops in

Kenya, each with 10 to 50 hawkers, sell pirated music. The number

of street hawkers distributing counterfeits range from 6,300 to

31,500. They are informally organised and each knows his or her

territory.

Major entry points for

pirated music are Malaba – from Uganda – and Mombasa and Dar es

Salaam. The latter get large consignments from Pakistan, India and

Dubai though panya (illegal) routes for distribution

locally. The three Asian countries are black-listed as the most

notorious duplication points.

Andrews says: "The

majority of pirated music in Kenya comes from Pakistan. These are

not small-time duplicators. We are talking about main pressing

plants that will run 5,000 to 20,000 copies of stolen music."

In April this year, the

International Federation of the Phonographic Industry closed down

six illegal plants in Pakistan. Piracy levels went down, but only

for a while. "It seems like the pirates have found new channels

and are back in business," says Andrews.

Closer to home, the

report takes issue with Uganda. It names Lucine, Salie and

Kasiwukira studios as major points of counterfeit music that ends

up in Kenya.

Both MSCK and AI Records

say Uganda is a source of illegally reproduced albums that are

crippling Kenya's music industry. "Uganda has weaker controls on

pirated music," says Andrews. It is a fertile ground for

duplication of new releases.

There is also a range of

small-time Kenyans who copy music at home or in informal settings.

"It is not possible to estimate the volume of this business, but

it is relatively small when compared to the more organized

reproduction and distribution system of music into Kenya from

Uganda," says the World Bank report.

Olang says these

informal outfits in Nairobi and Mombasa can reproduce up to 70,000

copies a night. "They have towers of equipment to do this. Their

go downs can be compared to vegetable markets. Hundreds of people

swam these places every morning to collect stocks."

Unconfirmed reports say

thieves have a way of laying their hands on a master copy of a new

release before it hits the market. "These copies are sold to

pirates through the back door soon after a recording," says

Andrews.

They are then taken to

pirates in Uganda and Asia. Large volumes of fake copies are

aggressively channeled through organised networks, denying

artistes and the Government large sums of revenue.

Some artistes may

inadvertently give master copies of their productions to

unscrupulous people, presumably for promotion purposes.

The third method of

reproducing music is quite obvious, but it works well for pirates.

They quickly buy a genuine copy of a new release and send it to

Pakistan, Malaysia, China or Singapore for reproduction.

"In two to four weeks,

pirated copies are available in Nairobi and elsewhere," says the

World Bank document.

It adds that the three

Ugandan companies send pirated music to at least eight

distribution centres in Kenya. Each of these centres have

distributors "who channel the music to sub-distributors".

Estimates by the MCSK

have it that more than 29 million pirated cassettes and CDs flow

through Kenya annually, generating approximately Sh5 billion. Part

of the proceeds is channelled to other illegal activity like drug

trafficking and crime.

Piracy stifles Kenya's

economy. Statistics from the World Bank say it accounts for

Sh1.3-5 billion in lost retail revenue to artistes, and Sh204-760

million in lost taxes to the Government annually. Lost royalty is

put at Sh140 million a year.

Andrews says this

plunder can be stopped tomorrow if administration of the Copyright

Act was moved from the A-G's chambers to the Ministry of Trade and

Industry. "The trade minister is willing to help," he says.

The Copyright Office

says efforts are being made to give the board autonomy, but this

may take some time as money will be required.

Article by Elly Wamari.

Sources: Nation Newspapers -

NationMedia.com

|

![]() COMMENTS

| PHOTOS

|

EVENTS |

COMMENTS

| PHOTOS

|

EVENTS |![]() MIXOLOGY

MIXOLOGY![]() |

|![]() VIDEOS |

ARTICLES

VIDEOS |

ARTICLES

![]()

![]() |

CONTACT

|

LOGIN

|

CONTACT

|

LOGIN

![]() |

REGISTER

|

REGISTER

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()